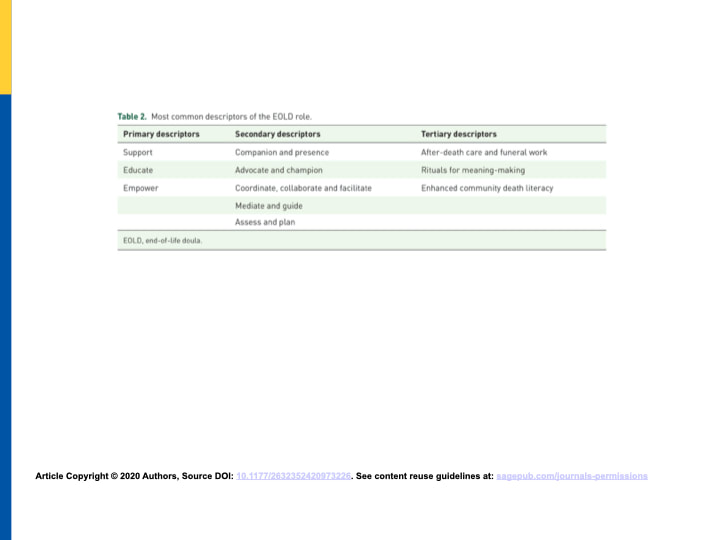

My research collaborator, Dr. Marian Krawczyk of the University of Glasgow End-of-life Studies Group, and myself have recently published an open-access article on the research we did on the end-of-life doula (EOLD) role in four countries. There has been a lot of interest in this work, including a recent town hall with the International Federation on Aging. We are keen to discuss our findings with the broadest audience possible, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic where end-of-life doulas are providing innovative services to address the myriad needs of families caring for dying individuals. We conducted 22 semi-structured interviews with key innovators and pioneers in the EOLD movement, five each from Australia, and the UK, and six each from Canada and the US. Some of the things I found most interesting about our findings are the broad range of descriptors of the EOLD role (see Table 2, below), the emphasis on community care and responding to the needs of the individual/family rather than imparting one’s own values, and the tension between mainstreaming EOLDs while preserving individuality and integrity as companion and advocate. More papers and more research will emerge from this data, including why the movement has gained such momentum, issues of professionality, standardization and regulation, women’s work, training, and much more. I hope you’ll read it and let me know what you think!

0 Comments

We all know that we live in a death-denying culture. Talking about and preparing for death is not something most people do. Here's a few pointers that I have learned from experience, that may help you do some self-examination and alter your approach to talking with others: I have learned:

The Dying Year made a positive impact in 2020!

What a year it has been. All of the turmoil and pain of the multiple pandemics and the death and loss we have experienced has exposed many cracks in our lives and in our systems. It is my sincere hope that some light may shine through the cracks on you and your loved ones as we come to the close of this tumultuous year and begin the new one. During the hardships of this year, we at The Dying Year have made an impact as we have done our best to create safe spaces to increase awareness and learn and grow together. Our aim is to help us all be better end-of-life caregivers. We will continue on this journey to learn to talk about difficult and uncomfortable issues. When this company began in March we were immediately thrust into helping EOL doulas adapt to the realities of providing Covid-appropriate care. Then our greatest change began when George Floyd was murdered. I (Merilynne) and many other white-identified people started examining, and stepping out of, the selfish and self-protective bubbles we had constructed, into a deeper awareness of oppression, white-supremacy, and systematic and institutional racism. Through all of this, we have been looking at how our biases and practices affect our work. What a growth year it has been! Some of the things I have learned include how to:

2020 Classes Jess, Toula, Robin, Olivia, Star and Merilynne taught four series of end-of-life doula trainings to 41 students. Three students have received their EOL doula certification and nine more are on their way! Merilynne taught five Advance Care Planning Facilitator trainings and certified 8 facilitators through the Respecting Choices® program. Kim Adams and Merilynne taught 19 people how to help families care for their own dead at home in the hours and days after death at the Home Funeral/Green Burial workshop. Wednesday discussions On average, twelve people attend our Wednesday EOL doula open discussions every week, where we explore many diverse topics, from building business skills to examining implicit bias to working in various care settings to Alzheimer’s care. This group has become quite a nurturing space for us to share and learn together. We welcome you, we honor you, we strive to see you as complete and whole, with your own answers, as someone who can contribute to us all, and who deserves to be treated with respect and dignity. Many thanks to Rachel Briggs for her steadfast and dedicated assistance in keeping this group going. Networking and community building is a primary focus of this group and all are welcome to attend, no matter where you are on your journey of becoming. If you would like to contribute a topic or be a speaker, please let us know! Research A primary accomplishment has been the publication of EOL doula research. Merilynne began a collaboration with academic researcher Dr. Marian Krawczyk in the fall of 2018. In 2019 we interviewed 21 EOL doula pioneers in four countries (Australia, UK, Canada and USA) about the EOL doula role and services provided, as well as thoughts on professional development and challenges within the field. “Describing the end-of-life doula role and practices of care: Perspectives from four countries” was published December 7 in the Journal of Palliative Care and Social Practice. This contributes greatly to the very slim body of research about our growing profession. At The Dying Year, our goal is to continue to bring together EOL doulas from all backgrounds, locations, and experience levels to help grow this profession. We are very grateful to Marta Bartholomew, our new virtual assistant, for coming on board in December to help with this work! The more doulas there are, the more people there will be having doulas. We are needed now more than ever and we need not struggle alone in our communities. Please join us however you are able! Becoming a member of Patreon is the best way to get involved and support The Dying Year, and in so doing, support and nurture yourself on your journey. Bless you! And Happy Holidays! Love, Merilynne and everyone at The Dying Year  On Tuesday, January 19 and 26, from 7-8:30 pm EST/4-5:30 pm PST, I am so pleased to host guests Marilyn Ababio and Kimberly Habi from Comfort Homesake in LA to talk about Soul Injury and Soul Healing for Caregivers. I met Marilyn at a ReImagine event in the summer and was struck by her wisdom and gentle heart. We’ve been wanting to do an event together for a while and here it is! We all have a spectrum of wounds that injure our souls. Our circumstances differ but the results can be devastating: avoidance of pain, debilitation, separation from our “real self.” We feel defective. To come into our power and heal, we need to restore ourselves, change our lives, and acknowledge what has hurt us. As we look at our pain, develop a relationship with it, listen to it, and re-own it, we can disarm our hearts and “re-home” our pain and break down our barriers. In this presentation we will learn some practical techniques to do this important work, lead healthier, more authentic lives, and transform our losses into living consciously in alignment so we can be peace-makers. I hope you will join me to learn from these two brilliant women; it will help us all be better caregivers, both for ourselves and for others at end-of-life. Don’t wait to do this awesome, vitalizing work. Register once for both presentations. The cost is $15 – 30 sliding scale, but no one will be turned away for lack of ability to pay – just contact me. You will be sent the zoom link when I receive your payment. Patreon Contributors, Supporters and Sponsors receive discounted registration. Marilyn and Kimberly's bio's can be found on the homepage. I believe the end-of-life doula profession is here to stay. However, I think it will continue to change and develop, and every EOLD practice will look different. There are too many variables for a one-size-fits-all practice model. Different communities and populations need different services, and different EOLDs have different strengths and skills they want to offer. In addition, the fact that we do not have an agreed upon definition or set of standards makes it difficult to educate the public about EOLDs so that they can be utilized. How do we fix all this? I don’t know, but I have some ideas. What do you think? Take the short survey here and receive the article "Full Moon Funeral" for free!

I recommend that doulas start by offering services that are already known about and in demand. In my experience, I have found that people want these things:

For example, I see a lot of students entering the profession because they are interested in sitting bedside and vigiling during active dying. But how realistic is it that a family will be comfortable inviting a stranger in to such a profound, emotional and private setting? If this is one of the aspects of doula work that draws you, you may need to become known in your community through offering other services. I’d love to know your thoughts. Please fill out this short survey for anyone interested in EOLD work (aspiring or experienced). How do you feel about what I have said? What services do you (want to) offer? Everyone who submits their responses will receive a complimentary copy of an essay I wrote entitled “Full Moon Funeral,” about the first home funeral I attended in 2009. Thank you so much — I can’t wait to hear from you! Join us every Wednesdays at 12 pm Eastern/9 am Pacific for discussion from other EOLDs. Register here to receive the link. You never see photos of a home funeral that depict someone doing paperwork; it is not the part of a DIY funeral that is visualized or sentimentalized in education. In a completely DIY home funeral, somebody close to the family must obtain the death certificate, fill it out properly, track down a physician to sign it, and file it manually with the county clerk, among other things. If the person died in a care facility or hospital, paperwork must be completed before the body can be released to the family and taken home. Equipment, several strong people, and a large vehicle are required to transport the body to a home, and to final disposition. Very few families will be able to do all of these tasks. If they don’t, is it still a home funeral?

Many natural death care educators emphasize a completely DIY home funeral. I believe that we need to broaden our scope and simplify our message. Most people benefit from spending time with the body of their deceased loved one after death, even if they do not take on the other aspects of death care, and do not call it a ‘home funeral.’ (The problem is, there is no catchy name for it.) Let’s educate people that they can simply be with the body in the early hours after death in many circumstances*, even if they do not do anything else in the care. Let’s not just educate about home funeral. Our message needs to be broader. For example, in the care facility where she died, my husband sat with the body of his mother for four hours after her death, during which time he prayed, cried, sang, anointed her and held her. No-one would call this a home funeral, but he did what he needed to do and benefitted greatly by it. It was a precious, sacred time of which I was privileged to be a part. Other family members were invited but did not attend. When my uncle died, close family members gathered in his room in assisted living. The hospice nurse invited us all to help wash and dress him. It was a cool November evening and we were told that for the next 24 hours we did not need to do anything beyond opening the windows and keeping the room cool. Without having planned ahead of time, one thing just led to another. We gathered the following morning to pray, sing, tell stories and comfort each other. We invited a larger circle of friends for an afternoon “open house” where we served coffee and cookies. Twenty-four hours after he died his body was removed for cremation. I don’t think anyone would call either of these situations a home funeral, per se. But they were very meaningful; nothing else was desired or needed. How can we encourage others to know about choices such as these? By emphasizing DIY home funerals, are we making it too complicated for most families? Yes, everyone should have the option to do as much as they want when a loved one dies, but many do not want or need to do it all and can similarly benefit from simply being with the body for a while. Yet most people do not know they can do this, do not know to ask for it, and do not understand how it can benefit them. I believe it is unnatural to have to hastily say good-bye to the body, yet we have come to believe that that is the only option. Many will benefit from simply spending time with the body for a little while, even if they don’t do the other aspects of the funeral care. It does not appeal to, nor is it practical for, everyone to file paperwork, obtain dry ice, wash, dress and cool the body, have a days-long visitation, take the body to the crematory or cemetery, etc. For those who want to do these things, it should be possible, but not doing these things is also very beneficial. Let’s find a way to also educate people about the benefits of being with the body, without calling it a home funeral. "Home funeral" = Beautiful, beneficial, difficult, requires planning and resources, not practical for many families. "Spending time with the body" = Uncomplicated, spontaneous, simple, practical, beneficial. *This article speaks about deaths that are expected and that occur from an illness, such as the death of someone in hospice care or someone who lives in a nursing home or was cared for in a hospital. In the case of an unexpected, sudden, accidental or violent death, the circumstances are quite different; it can be very difficult to spend time with the body immediately after death. Often emergency personnel are involved and the family does not have immediate access to the body of their loved one, which adds to the tragedy. Death care educators should address this in education and help prepare students to be available to the family, liaise with officials, increase communication, and assist where possible, such as by viewing the body and reporting to the family, obtaining personal effects, or being a witness to or helping in the loving care of the body. In these tragic circumstances, we can be creative in assisting the family in other ways, such as gathering mementos, creating memorialization opportunities and ceremony, and being a helpful presence in grief and bereavement.  Listen to webinar here. The end-of-life doula (EOLD) field is a rapidly growing profession that is not currently regulated. Many who are drawn to caregiving at the end of life are exploring death doula/death midwife training. With 10,000 boomers turning 65 every day in the US, we need creative ways to care for the elderly and the dying at home. Is certification necessary to set up a business and work as an EOLD? I’ll be discussing this on Wednesday, April 29, at noon EDT, in a zoom webinar that is open to all; email me to receive the link. Credentialing by an independent professional organization may be on the horizon in a few years. Currently, however, it’s important to understand that certification is conferred only by independent trainers or training organizations. In other words, individuals certify their students according to what they independently have decided are the necessary knowledge, skills, and/or experience to have. Among different trainers and training programs there is great diversity of style, philosophy, and content with no professional oversight of any kind. Let me give you an example. Mr. Z, an entrepreneur, decides he wants to offer EOLD training. He’s had life experience or professional experience that he, with no sanction by any other professional body or group of people, think qualifies him to offer such training. He designs his class or course based on his definition of an EOLD and what he thinks the role entails. He then also decides to offer certification, based on a process that he made up. It may include field experience, it may not. It may include a test or written assignments, or not. He decides to confer a credential. A common credential currently used by many trainers is CEOLD - Certified End-of-LIfe Doula. But here’s where it gets tricky. Someone who earns a CEOLD from his certification program does not compare with someone who earned a CEOLD from another training program. Ms. A’s training program may use an entirely different definition of what an EOLD is and does. Ms. A may include a different skill set and philosophy. No outside regulatory body that has sanctioned or compared either program, but they may use the same CEOLD credential. This is confusing to students, EOLDs, consumers, and healthcare organizations alike. The benefit to the student of obtaining certification is that they know their knowledge and skills compare to someone else who is certified by the same training organization. The drawback is that it means nothing overall until there is some oversight of training organizations by an independent professional organization. There is one organization that is not a training organization that confers a credential — the National End-of-Life Doula Alliance (NEDA). It is called a proficiency badge and it is open to anyone, regardless of training background. It assesses knowledge only, not skills or experience, and is based on a set of core competencies defined by a consortium of EOLDs and trainers. It provides a first step in bringing everyone together to define this profession. and it sets the stage for a more robust regulatory process to come. Join me to discuss this further. Bring your questions and concerns and ideas. By sharing our views and hashing this out, we’ll help move this profession along. I’m interested to know what you think. I heard the most amazing story yesterday. A couple of months ago, my friend Mickey was called to the hospital room of her 85-year-old aunt who was severely ill with chronic respiratory illness. As her aunt struggled to breathe, she kept expressing the wish to just go home. She was highly agitated and expressed this to the hospital staff who were at wits end to calm her down. The young physician who was treating her was adamant that she needed to undergo a treatment plan that consisted of indefinite hospitalization, tests and monitoring. Her aunt wanted none of it. She was scared, she was extremely uncomfortable, and she felt she wasn’t being heard. Things escalated to the point where the doctor told her that if she left the hospital, she would be leaving “AMA” (Against Medical Advice) and would possibly have to foot the bill.

Thankfully, Mickey was able to advocate for her aunt. “It seems we have a communication problem,” she said to the doctor. “My aunt doesn’t know you, she doesn’t understand you, and she hasn’t had the time to build trust with you. Would you be willing to speak with her primary care physician, in whom she has confidence?” she asked. The hospital doctor said yes, and they spoke, and also included her aunt on the call. This made everyone feel better; it created a sense of teamwork and shifted the focus to her aunt’s needs. It also became evident that although the paperwork concerning her aunt’s end-of-life care wishes was sitting at the bedside, it had not been filled out, and the care team did not expressly know which life-saving procedures she did or did not want. Mickey read the documents aloud to her aunt and ascertained her wishes, which included a preference that no extraordinary measures be taken to prolong her life. Her aunt signed the documents in the presence of a hospital chaplain and her wishes were made known to the entire care team. Brilliantly, at this point, it occurred to Mickey that, rather than simply refusing the type of treatment plan the hospital doctor wanted, they could choose a different type of treatment plan that focused on comfort, like her aunt wanted. Mickey knew to involve the hospital social worker in order to ask if her aunt could go home on hospice care. This is when the real shift occurred. The social worker advocated for this, and everyone agreed. Plans were made, and even though her aunt died before she could get home, she died peacefully in her sleep, knowing that going home was the eventual plan. You are reading this because you are participating in a massive paradigm shift. You want to prevent scenarios like the one in this story. You want to be there for your people and for your community. Mickey’s aunt, fiercely independent all her life, was too sick to orchestrate the end of her life the way she wanted. She needed Mickey to speak up, pivot the discussion, and not be afraid to mention the h-word. The end-of-life doula role encapsulates this. The movement is growing at an incredibly rapid pace because we are in a specific point in time where the skills that doulas learn are very needed. Doulas are available, they show up, they listen, they use problem solving skills, they bring in all available resources, they have knowledge. Does one have to have taken end-of-life doula training to do what Mickey did? No, in fact, she didn’t. Thankfully, she had other life experiences that came to the fore and equipped her with the ability and the confidence to be there for her aunt. But end-of-life doula training, like no other single one profession, focuses on these specific skills and brings them together in a systematic approach, equipping graduates to help in moments such as her aunt’s hospital crisis. And it is immediately accessible, affordable, and achievable. You are called. You are needed. Answer the calling and be an end-of-life doula. It’s a great way to help change the way we die at this point in time. It gives you a community of game changers to learn with and gain energy and inspiration from. The world doesn’t really know about us yet, but it will, as we take these skills and this drive to be of service into our communities in whatever way we can. My goal is to help you discern that, to hear your stories, to pass them on, and to be a resource to you as you change the world. Let me know how I can help you. by Merilynne Rush

Suzie, a 39-year-old single mother of two teenagers, is dying of a rare degenerative disorder and is in hospice care. She lives alone (her children live with their father) in a small apartment near her boyfriend and her mother, who share in her care. She is lonely and needs companionship and support. A friend heard of end-of-life doulas and suggested the idea to her. Alfred has cancer and has been told he can expect no more than a year to live; he is not yet in hospice. His goal is to make it to his 25th wedding anniversary in six months. He feels fine and is putting things in order, but as his symptoms worsen, he does not want to be a burden on his family. He wonders how an end-of-life doula can help. Marion recently moved to Michigan to be near her aging mother who is very frail and has started receiving hospice care. Her mother lives alone and has several caregivers, but Marion thinks more services may be needed soon. She asks if an end-of-life doula can arrange to visit once a week for now. I am blessed to be able to talk to people who are grappling with death. Mostly, I speak with the caregivers. They reach out to me because they feel like there is no one else to talk to. I am there. I listen. I understand. I hear them out and empathize and honor them. It is difficult being a caregiver; it can feel so lonely, especially when you just want to talk. I recently heard a quote from Cheryl Richardson, “People start to heal the moment they feel heard”. Perhaps that is the biggest role of the end-of-life doula – to hear. In a world that prefers to deny death, when death IS happening, we want to be heard. How is talking about death a blessing to me? People ask me this all the time. When I talk about facilitating the Death Café, or when I speak about being an end-of-life doula, people wonder if it isn’t depressing or morbid. Actually, the opposite is true. Finding meaningful work helping others navigate life’s most challenging transitions fills me with a sense of purpose greater than myself. I feel as though I am in the right place at the right time, being privileged to witness the awesome emotion, connection, and healing that can take place. This was true of being a birth midwife as well. For all of my life, first as a birth midwife, and now as an end-of-life doula, I have been gifted with being able to help others during life’s most awesome moments. At a birth, or at a death, it is clear who is doing the hard work, and it is not me. My job is to accompany, to listen, and to guide. I pass on knowledge that others have taught me. I am a conduit. And when it’s over, I leave. I go out into the world and live my life. I feel truly alive and uplifted. I may be exhausted, but usually I’m exuberant. The formal definition of an end-of-life doula (EOLD) is someone who provides non-medical, holistic support and comfort to the dying person and their family, which may include education and guidance, as well as emotional, spiritual or practical care. EOLDs engage with clients from as early as initial diagnosis through after death care and bereavement. When caregivers are feeling overwhelmed, the doula helps identify physical, emotional, spiritual, and practical needs and ways to meet them. The word doula means service. Most people are familiar with the term as it is used for birth and postpartum care. All doulas provide non-medical, non-judgmental, empowering support, guidance and hands-on assistance. In addition to listening and accompanying, the services an EOLD provides may include:

The end-of-life doula works closely, and in collaboration with, the interdisciplinary palliative or hospice care team. S/he may practice independently and contract directly with the individual or family, or s/he may be part of the services that a hospice agency offers. Compared to a hospice volunteer, the EOLD has more training, is available for longer periods of time, and provides a greater range of services. The thing is, I’m working with people who are embracing that death is happening. They want to be prepared, to accept, to be fully present, not to fight, to fix, or to deny. By doing this, they are going against the cultural norm, and this is why they may feel alone and need support. The end-of-life doula is grateful to be contacted by a family member or friend who is struggling and wants to talk. S/he recognizes the opportunity to make a difference and help improve the quality of life for both the dying person and their loved one(s). The doula has grappled with loss before and knows that to move through it, one needs a friend. Perhaps a better definition of an end-of-life doula would be: A knowledgeable, experienced, temporary friend who provides compassion and isn’t afraid to talk about the tough stuff.  I know many of you are not making in-person visits to your clients, family and friends right now. Here are a few ideas for being a remote end-of-life doula, based on my personal experience. #1 Stay in Contact Those who live alone or have minimal social support need contact, in some form, now more than ever. Remember, “Kindness and compassion can be felt from a distance.” (Diana Cramer) For those who work in care facilities, please spend as much extra time with patients as you can, because their regular visitors can’t be there. Ask them about the photographs in their room, or any other object that gives you a window into who they are. If appropriate and safe, touch them, hold their hand (even if you are gloved), offer to rub lotion on their arms. Help them put on soothing music. Whatever you can do to provide new sights, sounds, smells and touch, even if for just 20 minutes a day, will help. This is especially important if they are not able to talk on the phone or online with those who care about them. If the care recipient is able to talk on the phone, call daily to check in. Be creative and think of ways to help them get stimulation them through the senses. This can improve mental health and help keep them connected to the outside world. If the care recipient is able to connect online, now is a great time to explore Google Hangout or Duo, Facetime, Skype, Zoom, Free Conference Call, or another platform by which they can see and talk to you. Some of these platforms work well for connecting multiple people, like grandchildren who live remotely. Teach yourself first, then ask an employee in the facility to help them get set up or, if they are able, talk them through the set-up yourself. I caution you to take your time and be patient! This may take several hours and/or several tries, but it will be worth it in the long run. Research and suggest online offerings. Many groups and organizations are establishing online programs like religious services, support groups, group chats, book clubs, inspirational webinars, and even online meditation! There are new options cropping up daily for a variety of interests. Remember, for someone who is very ill, keep it simple. #2 Doula-ing Remotely We may not be able to visit in person, but some of our EOL doula talks and tasks can be accomplished remotely, such as Advance Care Planning discussions, life review (asking questions and recording the answers, doing research for a project like a book or an album), coming up with a list of questions for the healthcare provider, review of symptoms and suggestions for non-medical comfort measures and, of course, simply checking in. Those who are elderly and/or very ill need perspective and help discussing decisions. They need a sounding board. Doulas do not give medical advice or diagnose, but we can provide information and validation. If symptoms sound serious, it is perfectly okay to say so and suggest contacting a medical care provider. Familiarize yourself with the telehealth options that are available. Ask your client if they would like you to look into this for them, based on the type of insurance they have and who they see for primary care. Again, you are not providing medical care yourself; you are enabling them to get a type of medical care they may not be aware of or familiar with. |

|

Speak with Merilynne about |

Find A TRAINING for |

find resources |

Website designed by Lee Webster, Side Effects Publishing

|

MAKE A DONATION to support the work of The Dying Year that helps other just starting out in the end of life doula field. Thank you!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed